En una entrada previa, se hizo una introducción al concepto de contrapunto doble o contrapunto invertible.

En resumen, se trata de tener dos líneas en contrapunto de manera que, invirtiéndolas verticalmente, sigan funcionando como contrapunto en todos sus sentidos.

In a previous entry, we introduced the concept of double counterpoint or invertible counterpoint.

In short, the idea is to have two lines in counterpoint in such a way that, by inverting them vertically, they continue to function as counterpoint in all their senses.

Esta técnica no se utilizó de forma "masiva”, pero si con frecuencia, ya que es muy útil para utilizar la inversión del material como nueva frase, etc. Vemos este ejemplo de J. S Bach:

This technique was not used in a "massive" way, but frequently, since it is very useful to use the inversion of the material as a new phrase, etc. Let's see this example of J. S Bach:

BACH, INVENCIÓN Nº 9 EN Fa menor, BVW 780

Observemos cómo tras los cuatro primeros compases las líneas se invierten, la que estaba arriba pasa debajo (una octava abajo) y la que estaba debajo pasa arriba (dos octavas arriba). El número de octavas no afecta al resultado de la inversión.

Notice how after the first four measures the lines are inverted, the one above goes below (one octave down) and the one below goes above (two octaves up). The number of octaves does not affect the result of the inversion.

Este tipo de contrapunto puede realizarse teniendo muy en cuenta cómo se comportan los intervalos cuando se invierten, dado que intervalos consonantes, pueden ser disonantes al invertirse.El contrapunto doble puede invertirse a distintos intervalos, lo más frecuente es la inversión a la octava, pero también es posible hacerlo a la décima o a la decimosegunda, incluso a otros intervalos que resultan menos efectivos y dificultosos.

En este momento vamos a desarrollar el CONTRAPUNTO DOBLE O INVERTIBLE A LA OCTAVA.

Lo primero a tener en cuenta es cómo se invierte cada intervalo:

- Cuando tenemos un unísono, al subir una nota una octava, el intervalo se convierte en octava

- Cuando tenemos una segunda, al subir una nota una octava, el intervalo se convierte en séptima

- Cuando tenemos una tercera, al subir una nota una octava, el intervalo se convierte en sexta

- Cuando tenemos una sexta, al subir una nota una octava, el intervalo se convierte en tercera

- Cuando tenemos una cuarta, al subir una nota una octava, el intervalo se convierte en quinta

- Y a partir de aquí los intervalos son equivalentes: al invertir la 5ª tenemos una 4ª, al invertir la 6ª tenemos una 3ª, al invertir la 7ª tenemos una 2ª y al invertir la 8ª tenemos un unísono

This type of counterpoint can be performed taking into account how intervals behave when inverted, since consonant intervals can be dissonant when inverted.

The double counterpoint can be inverted to different intervals, the most frequent is the inversion to the octave, but it is also possible to do it to the tenth or to the twelfth, even to other intervals that are less effective and difficult.

At this point we are going to develop the DOUBLE CONTRAPUNTO OR INVERTIBLE TO THE EIGHTEENTH.

The first thing to keep in mind is how each interval is inverted:

Si el intervalo es compuesto (octava + tercera = décima, octava + cuarta = undécima, etc...) e intervalo resultante es el mismo, solo que las voces pueden haberse cruzado.The double counterpoint can be inverted to different intervals, the most frequent is the inversion to the octave, but it is also possible to do it to the tenth or to the twelfth, even to other intervals that are less effective and difficult.

At this point we are going to develop the DOUBLE CONTRAPUNTO OR INVERTIBLE TO THE EIGHTEENTH.

The first thing to keep in mind is how each interval is inverted:

- When we have a unison, by raising a note an octave, the interval becomes an octave.

- When we have a second, by raising a note an octave, the interval becomes a seventh.

- When we have a third, when we move up one note one octave, the interval becomes a sixth

- When we have a sixth, when we move up an octave one note, the interval becomes a third

- When we have a fourth, when we move up one note an octave, the interval becomes a fifth.

- And from here the intervals are equivalent: when inverting the 5th we have a 4th, when inverting the 6th we have a 3rd, when inverting the 7th we have a 2nd and when inverting the 8th we have a unison.

Por ejemplo en este caso la décima del compas 3, al invertirse de un modo u otro da lugar a un entrecruzamiento de voces, sin embargo el intervalo resultante (?) es una tercera, solo que invertida (algunos lo marcan con un signo - para indicar que las notas se han cruzado).

Algunos autores clásicos recomiendan que el contrapunto inicial no se separe entre sí más de una octava, para que no dé lugar a cruzamientos de las líneas melódicas al invertir. Pero otros son más tolerantes con este aspecto.

If the interval is compound (octave + third = tenth, octave + fourth = eleventh, etc...) the resulting interval is the same, only the voices may have crossed.

For example in this case the tenth of bar 3, when inverted in one way or another gives rise to a crossing of voices, however the resulting interval (?) is a third, only inverted (some mark it with a - sign to indicate that the notes have crossed).

Some classical authors recommend that the initial counterpoint should not be separated by more than an octave, so that the melodic lines do not cross when inverted. But others are more tolerant with this aspect.

La segunda cuestión importante es saber qué intervalos son consonantes y cuáles no y, por tanto, cuáles son los que debemos usar pensando en una inversión.

For example in this case the tenth of bar 3, when inverted in one way or another gives rise to a crossing of voices, however the resulting interval (?) is a third, only inverted (some mark it with a - sign to indicate that the notes have crossed).

Some classical authors recommend that the initial counterpoint should not be separated by more than an octave, so that the melodic lines do not cross when inverted. But others are more tolerant with this aspect.

La segunda cuestión importante es saber qué intervalos son consonantes y cuáles no y, por tanto, cuáles son los que debemos usar pensando en una inversión.

En el contrapunto clásico se consideran consonancias perfectas el unísono/octava y la quinta justa.

La tercera y la sexta (mayores y menores) se consideran consonancias denominadas imperfectas (porque no parten de intervalos "perfectos", no porque suenen peor).

La cuarta, la segunda y la séptima se consideran disonancias.

Otros intervalos (aumentados, tritonos...) son altamente disonantes y solo en circunstancias concretas se utilizan. Véase la siguiente entrada sobre esta cuestión: Consonancias y Disonancias.

Siguiendo las normas básicas del contrapunto, debemos favorecer los intervalos de tercera y sexta (que pueden ir encadenados sin problema) y menos frecuentemente los intervalos de quinta, unísono y octava. El resto de intervalos se pueden usar, pero siempre y cuando actúen como notas auxiliares, notas de paso o como las queramos denominar. Véase esta entrada sobre notas de paso: Notas ajenas al acorde.

Cuando invertimos a la octava, como hemos señalado antes, obtenemos los siguientes intervalos:

Cuando invertimos la octava o el unísono, obtenemos igualmente una consonancia perfecta.

Cuando invertimos la sexta o la tercera, obtenemos igualmente una consonancia imperfecta.

Cuando invertimos la segunda o séptima, siguen siendo disonantes (descartadas como notas principales).

El "problema" lo tenemos con la quinta, dado que, al invertirse, queda como una cuarta que es disonante, por lo que no podemos usar las quintas como notas relevantes, en tiempos fuertes, etc.

Esto significa que tenemos que tratar las quintas como si fueran disonancias, ya que al invertirse se quedarán como cuartas disonantes.

The second important question is to know which intervals are consonant and which are not and, therefore, which ones should be used in an inversion.

In classical counterpoint, the unison/octave and the just fifth are considered perfect consonances.

The third and the sixth (major and minor) are considered imperfect consonances (because they do not start from "perfect" intervals, not because they sound worse).

The fourth, second and seventh are considered dissonances.

Other intervals (augments, tritones...) are highly dissonant and only in specific circumstances are they used. See the following entry on this issue: Consonances and Dissonances.

Following the basic rules of counterpoint, we should favor intervals of third and sixth (which can be chained without problem) and less frequently intervals of fifth, unison and octave. The rest of the intervals can be used, but as long as they act as auxiliary notes, passing notes or whatever we want to call them. See this entry on passing notes: Notes outside the chord.

When we invert the octave, as we have pointed out before, we obtain the following intervals:

When we invert the octave or unison, we likewise obtain a perfect consonance.

When we invert the sixth or the third, we also obtain an imperfect consonance.

When we invert the second or seventh, they are still dissonant (discarded as principal notes).

The "problem" we have with the fifth, since, when inverted, it remains as a fourth that is dissonant, so we cannot use the fifths as relevant notes, on strong beats, etc.

This means that we have to treat the fifths as if they were dissonances, since when inverted they will remain as dissonant fourths.

In classical counterpoint, the unison/octave and the just fifth are considered perfect consonances.

The third and the sixth (major and minor) are considered imperfect consonances (because they do not start from "perfect" intervals, not because they sound worse).

The fourth, second and seventh are considered dissonances.

Other intervals (augments, tritones...) are highly dissonant and only in specific circumstances are they used. See the following entry on this issue: Consonances and Dissonances.

Following the basic rules of counterpoint, we should favor intervals of third and sixth (which can be chained without problem) and less frequently intervals of fifth, unison and octave. The rest of the intervals can be used, but as long as they act as auxiliary notes, passing notes or whatever we want to call them. See this entry on passing notes: Notes outside the chord.

When we invert the octave, as we have pointed out before, we obtain the following intervals:

When we invert the octave or unison, we likewise obtain a perfect consonance.

When we invert the sixth or the third, we also obtain an imperfect consonance.

When we invert the second or seventh, they are still dissonant (discarded as principal notes).

The "problem" we have with the fifth, since, when inverted, it remains as a fourth that is dissonant, so we cannot use the fifths as relevant notes, on strong beats, etc.

This means that we have to treat the fifths as if they were dissonances, since when inverted they will remain as dissonant fourths.

La manera de tratar la quinta como una disonancia se basa en usarla como nota de paso, nota vecina o suspensión, aunque no veo por qué no en otros casos como notas de escape, etc. De todos modos el concepto es el mismo: 5ª = disonancia.

The way to treat the fifth as a dissonance is based on using it as a passing note, neighbor note or suspension, although I don't see why not in other cases such as escape notes, etc. Anyway the concept is the same: 5th = dissonance.

Analicemos este cantus firmus propuesto por Fux, en Re dorico, y la solución de Schubert como contrapunto invertible a la octava.

Let us analyze this cantus firmus proposed by Fux, in D doric, and Schubert's solution as invertible counterpoint at the octave.

Al haber utilizado solo intervalos permitidos en el contexto, la inversión es consonante. Así la octava se convierte en unísono, la tercera en sexta, etc. Observemos algunos entrecruzamientos de las voces al invertir, cundo el intervalo inicial es una décima.

Hay un solo punto en el que Schubert se salta la norma y es en el compás 5. Vemos que sobre la nota La, superpone un Do#, una tercera, dado que no puede colocar la nota Mi, ya que el intervalo formado La-Mi, siendo consonante, sería disonante al invertir (una cuarta). Tampoco puede colocar sobre el La la nota Re porque, independientemente de que al invertir fuera una quinta consonante, es directamente disonante en esa primera línea que propone. Por ello, coloca un Do# que forma una tercera consonante con el La, a pesar de que la nota se repite en el compás siguiente (Do#) lo cual no es lo ideal en contrapunto de primera especie. La cuestión es que, al invertir ese La-Mi, cambia la nota Do# por un Re, dejando el intervalo en una quinta.

Es como si hubiera escrito primero la línea inferior, con ese Re bajo el La, y al invertir forzara a que la nota bajara a la tercera Do#.

Having used only intervals allowed in the context, the inversion is consonant. Thus the octave becomes a unison, the third becomes a sixth, etc. Let's observe some interweaving of the voices when inverting, when the initial interval is a tenth.

There is only one point in which Schubert skips the rule and it is in measure 5. We see that on the note A, he superimposes a C#, a third, since he cannot place the note E, since the interval formed A-E, being consonant, would be dissonant when inverting (a fourth). Neither can he place on the A the note D because, independently of the fact that when inverted it would be a consonant fifth, it is directly dissonant in that first line that he proposes. Therefore, he places a C# that forms a consonant third with the A, even though the note is repeated in the following measure (C#), which is not ideal in first-species counterpoint. The point is that, by inverting that A-E, he changes the note C# to a D, leaving the interval in a fifth.

It is as if he had written the lower line first, with that D under the A, and by inverting it he forced the note down to the third C#.

There is only one point in which Schubert skips the rule and it is in measure 5. We see that on the note A, he superimposes a C#, a third, since he cannot place the note E, since the interval formed A-E, being consonant, would be dissonant when inverting (a fourth). Neither can he place on the A the note D because, independently of the fact that when inverted it would be a consonant fifth, it is directly dissonant in that first line that he proposes. Therefore, he places a C# that forms a consonant third with the A, even though the note is repeated in the following measure (C#), which is not ideal in first-species counterpoint. The point is that, by inverting that A-E, he changes the note C# to a D, leaving the interval in a fifth.

It is as if he had written the lower line first, with that D under the A, and by inverting it he forced the note down to the third C#.

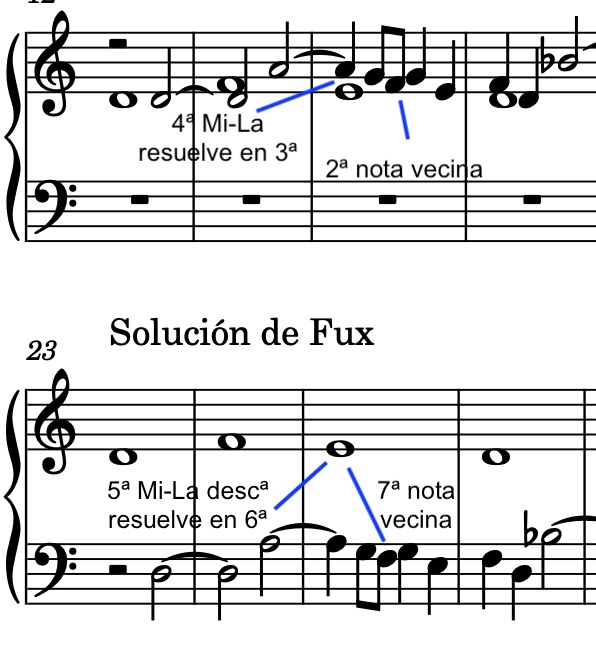

Veamos ahora otro cantus firmus de Fux y la solución del mismo compositor.

Let us now look at another cantus firmus by Fux and the solution by the same composer.

Observemos como Fux sí utiliza (en el contrapunto inicial) intervalos disonantes, incluso segundas, cuartas y séptimas. Pero so siempre en posiciones débiles o preparados y resueltos debidamente. Por ejemplo:

Fux toma el camino más sencillo. Solo utiliza una quinta casi a final, sobre la nota Sol hay un Re que es nota vecina de la sexta consonante Mi, y además, está en una posición muy débil. Al invertirse queda una 4ª como nota vecina de terceras bajo la nota Sol.

Fux takes the simplest way. He only uses a fifth almost at the end, over the note G there is a D which is a neighbor note of the consonant sixth E, and besides, it is in a very weak position. When inverted, a 4th remains as a neighbor note of thirds under the G note.

Note how Fux does use (in the initial counterpoint) dissonant intervals, including seconds, fourths and sevenths. But it is always in weak positions or prepared and properly resolved. For example:

Observamos cómo las 4ª y 5ª están en posiciones débiles y resuelven en nota consonante. Lo mismo ocurre con la nota vecina (antecedida y seguida de notas consonantes).

Observamos cómo las 4ª y 5ª están en posiciones débiles y resuelven en nota consonante. Lo mismo ocurre con la nota vecina (antecedida y seguida de notas consonantes).

We observe how the 4th and 5th are in weak positions and resolve in consonant note. The same happens with the neighbor note (preceded and followed by consonant notes).

--------------------

EJEMPLO APLICANDO EL CONTRAPUNTO INVERTIBLE A LA OCTAVA

EXAMPLE USING INVERTIBLE COUNTERPOINT TO THE OCTAVE

Siiiiiii…. ¡Una invencion! Por favor, haz una entrada explicando cómo hacer una. 🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻

ResponderEliminar